History

The graveyard has been a cemetery since time immemorial. It was used as a provisional cemetery after the ‘Battle of Debrecen’ on 2nd August 1849, and since that time onwards the local public have known it as the ‘Russian Cemetery’ and the Military Cemetery. From the beginning of the Great War, the soldiers of various nationalities who died in Debrecen hospitals were first buried in the town’s cemeteries belonging to religious denominations. The Military Hospital, enlarged with the Heroes’ Cemetery, was opened on 20th January 1915 to bury the victims.

Burials also took place here in 1919 and sporadically even in the interwar period. During WWII, soldiers, primarily German and Hungarian, who died in the local hospitals, and later those who died in POW camps, were interned here. The memorials erected in the cemetery and the Mausoleum, built in a central location, pay tribute to the identified and unknown soldiers who died a hero’s death in the wars of 1848-1849, 1914-1918 and 1939-45 and are laid to rest here.

After several additional internments, conversions and partial reconstruction, the municipality of Debrecen renovated the cemetery in 2017-2018 as part of the Military History Institute and Museum of the Ministry of Defence programme, coordinated by the Őrváros Public Foundation, with the professional and financial support of the Debrecen Militarium in commemoration of the centenary of the Great War.

Cemeteries for religious denominations and for victims of epidemics

Following the Catholic customs and the statutes, the inhabitants of medieval Hungarian settlements buried their dead in and around churches. This tradition was maintained in Debrecen too up until the Reformation, when, in the 16th century, cemeteries were moved outside the inhabited areas of the town. Thanks to the structure and the well-organised urban plan of the town, in the different ‘highly autonomous streets’ (1) the sites of the so-called “street” (Protestant) cemeteries were marked out beyond the town’s entrenchment that lay closest to the given area. Thus, cemeteries – which were typically named after their streets –virtually surrounded the inhabited areas. The earliest written record mentions the Czegléd (Kossuth Street cemetery, at the eastern boundary of the town: it is referred to in written documents dated 1572 as the “big cemetery”. (2)

In 1716-1717 a burial ground was designated for the Catholic inhabitants who moved back to Debrecen: it was located outside the town gate at Szent Anna Street, in the area once bordered by the two branches of the former Diószegi Road, i.e. today’s Vágóhíd and Budai Ézsaiás streets, next to Homokkert. This Catholic cemetery was later expanded with a part for military burials. It was closed down, along with other cemeteries, in the third decade of the 19th century, but its Baroque memorial funerary chapel, built in 1774, can still be found here. A new addition to denominational cemeteries took place in 1844, when the Israelite cemetery was established in the southwestern edge of Homokkert; now it is the only open denominational cemetery in Debrecen.

Cemeteries often needed to be provided for the burial of the victims of the various epidemics that took their toll in Debrecen. For example, four such cemeteries were set up in 1739 outside the gates of Mester, Péterfia, Csapó and Várad streets. Due to public health considerations, these cemeteries, which were relatively far from inhabited areas, were soon closed down, and only one or two were put to permanent use a few decades later.

Debrecen’s municipal records mention six operating cemeteries in 1777: five ’big’ cemeteries for the Protestants (in Hatvan, Péterfia, Boldogfalvi or Varga (Várad), Csapó and Cegléd streets) and the Roman Catholic cemetery in Szent Anna Street. (3) most of these are now built-up residential areas, and a few of them are burial sites, such as the area of the Csokonai sepulchral monument, which survived from the Hatvan Steet cemetery, and the hillock of the old Catholic funerary chapel. Scarcely any historical records are known about the maintenance of the cemeteries in today’s sense. The unused parts of the cemeteries were used after some time as new burial places, or, when the grounds became obviously scarce, new plots were put into use in the immediate vicinity of the old ones.

Military cemeteries

Debrecen’s military cemeteries were special burial places. Two separate military cemeteries were set up in the Szent Anna Street Catholic cemetery after a moderate enlargement of the grounds. The one situated on the northern pasture of Köntösgát was used in the third decade of the 19th century to bury the victims of the epidemic that raged among the WWI Russian POWs transported to Debrecen. The enclosed cemetery behind the water works wells was never opened for permanent use. The other, significantly larger military cemetery is the older one. It was known as the Military Cemetery from 1849, and (also) referred to as the Heroes’ Cemetery from the first decade of the 20th century. The burial site where the Hungarian and Russian dead of the tragic battle of Debrecen of 2nd August 1849 are entombed, was not used for almost seven decades, but was reopened during both world wars to bury the fallen soldiers.

The Military Cemetery

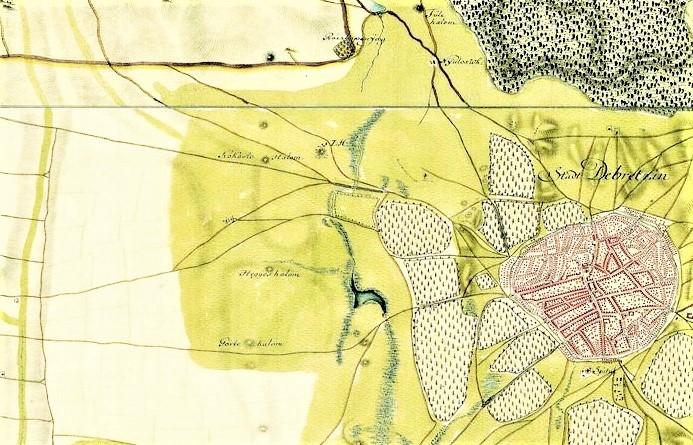

The location of the Military Cemetery was determined by the site of the 1849 battle of Debrecen between the handful of honved troops led by General József Nagysándor and the Russian troops, who outnumbered the Hungarians tenfold. The battle was fought 4-5 kilometres from the city centre: on the northern and southern pastures of Köntösgát (today’s Balmazújvárosi Road), on the pasture of Nyulas stretching to the Great Forest, as well as at the northern fence (entrenchments) of the Köntöskert and Csigekert parts of the town. The battleground could be accessed the fastest from the direction of the town, along what was then called Újvárosi main road, outside the Mester Street gate. This road began where the plot of today’s Reformed church is and ran along the western edge of Csigekert, along the line of today’s Military Cemetery; after the garden area it reached the Köntösgát dam, today’s Balmazújvárosi Road, which led outside the town across the bridge over the river Tócó.

Debrecen nyugati fele az 1849. aug. 2-i ütközet helyszíne (első katonai felmérés, 1783/85)

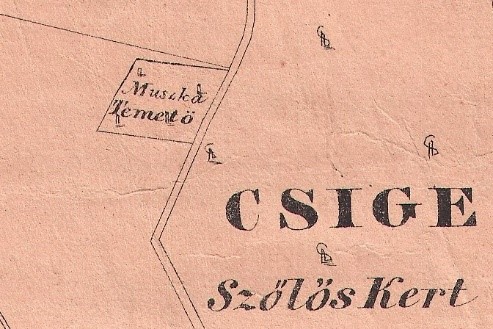

In retrospect it is hard to say to what extent the selection of the site of the Military Cemetery was a well-considered decision based on a thorough knowledge of the town’s local history, or if the decision-makers were aware of the map from 1812 that shows a “Plague Cemetery”? (4)

It is certain, however, that the people in charge back then did not know about the debates and guesswork related to a cemetery, which, based on the name of the street – Saint Michael (patron saint of the dead) – presumably existed centuries earlier in the western part of Debrecen in the vicinity of Csigedomb and the nearby Lake Csige, along with a Medieval church in the north-western part of Debrecen, within the trenches that surrounded the town. Neither archaeological research, nor written records provide irrefutable support for or against this theory. What we know (from Lajos Zoltai) is that the name of Szent Mihály Street occurred even in 18th-century official reports. It is interesting, however, why the inhabitants of Debrecen decided more than a century after the Reformation to keep ’saint’ in the case of Szent Mihály (Saint Michael) Street and Szent Mihály Hillock, when it had long been omitted from names containing Szent Anna (Saint Anne), Szent Miklós (Saint Nicholas) and Szent András (Saint Andrew)? It is highly likely that in Debrecen, like in other towns, the name of Saint Michael referred to an old burial ground. It seems that in the nation’s mind the cemetery, burials and Saint Michael were so deeply connected that even 4 or 5 generations could not delete it. (Szent Mihály Street mentioned in old documents referred to one of the streets within the town’s entrenchment, possibly to today’s Mester Street, while Szent Mihály Hillock must have been another name used for Csigedomb hillock, since Csigekert (Csige garden) was simultaneously described as ‘situated by Lake Csige’ and ‘lying under Szent Mihály hillock.) (5) Based on the above, it is safe to assume that there once was a cemetery on Csigedomb hillock.

After the battle on 2 August 1849 ended, the Russian headquarters allowed the soldiers of the victorious troops three days of pillaging and therefore closed off the entire area of the battleground; they only ordered the municipal authority to bury the dead on the fourth day after the battle.

The officials of the municipality of Debrecen had a great deal of experience in handling epidemics, since in 1831, i.e. less than two decades before the battle of Debrecen, 2,152 out of the 30,000 inhabitants of the town had fallen victim to an infectious disease. The burial places of these victims were marked out in a separate place, outside the town, around the sand hills; they were closed off to the locals for fear of the epidemic re-emerging and most of them were never again used as ’cemeteries proper’. (6) The leadership of the town also had to deal with the extreme threat of an epidemic breaking out in the sweltering heat of August 1849. They very probably had no time to seriously plan the selection of the site, and even less chance to take the historical research of the site into consideration.

A Csigekert melletti járványtemető 1812-ben (DVT 264 részlet)

Márton Szabó, the captain of the agricultural police entrusted with the burial of those killed in the battle, The Russian Cemetery on a map in 1850had the human remains of the 112 honved soldiers (7) and the 634 Russian soldiers buried near the battlefield: in a mass grave dug into the side of Csigedomb, at the western corner of Csigekert. (8) The sources are somewhat contradictory in regard to the numbers interred there, but most researchers agree that in addition to the men buried here on the fourth day after the battle and in subsequent days, thousands of Russian soldiers died in the various temporary hospitals set up across the town. No accurate data are known about their burials but it can be presumed that they were laid to rest in this new cemetery established for the victims of the epidemic. This theory is supported by the map of Debrecen dating to a few years later, in which the Military Hospital is marked as “Russian Cemetery”. (9)

A „Muszka Temető” az 1856-1860 között készült térképen (Ny 25 részlet)

At the beginning of August 1849, about 3,000 Russian soldiers were lying ill (10) in the buildings converted into improvised hospitals in Debrecen. The mainly cholera-infected patients were placed in the larger buildings, such as the Reformed college, the Saint Anne church and Piarist priory, the former Franciscan monastery (then used as a tobacco warehouse) in today’s court in Iparkamara Street, the Bekné apartment block in Piac Street (later converted into a two-storey building: today’s Tisza Palace), (11) The Russian Cemetery on a map in 1850the Oláh House in Csapó Street (firemen’s barracks up until the recent past) as well as in other, mostly municipal buildings. By the middle of the month, the number of patients increased to such an extent that royal commissioner Ferenc Drevenyák ordered the stone and wood ’huts’ – used for selling and storing products in the Külső-vásár district – to be opened up, and had the labourers and carpenters convert them for the 1,000 patients. The resulting hospital capacity was used up three days later, by 25th August, and the 500 new patients had to be put up in private homes and in shops. In the course of a few months, huge numbers of Russian soldiers marched through Debrecen in troops and stayed for shorter and longer periods. They only left behind the ill soldiers, who were still in Debrecen hospitals in April 1850. The last Russian soldier died in Debrecen on 23rd July 1850.

Military memorials

Grateful posterity strove to commemorate the war dead even amidst politically unfavourable circumstances. The impressive monument called ֞The Dying Lion”, forming part of the stairs of the mausoleum of the Heroes’ Cemetery was already completed in 1861 by sculptor János Marchalkó, who also sculpted the lions of the Chain Bridge in Budapest. The sculpture made of stone from Sóskút and originally intended for the tomb of hussar, Captain Szarka, who fell by the main road in Hosszúpályi, 12 was designed by Imre Komlóssy. 13 The composition was kept in a hidden location for six years, and was unveiled on 2nd August in the year of the Compromise at a commemoration ceremony on an artificial elevation in the Memorial Garden in front of the Reformed College, in the place where today’s Bocskai statue stands. The monumental memorial with a width of 4 metres and a height of 3 metres was transferred from here in 1899, on the 50th anniversary of the battle of Debrecen, to the military Cemetery, where it was placed at the highest point of the former Csigedomb. (14)

Honvédemlékmű a Csigedomb tetején (Déri Múzeum)

Thus, the heroic soldiers were commemorated by this memorial in addition to the red marble plaque above the mass grave, given as a gift by stone engraver Sándor Boros and unveiled on 15 March 1885. The inscribed monument can now be found on the right along the path leading to the Mausoleum. 15 Its inscription reads: “The defenders of our homeland, demi-gods lie here at rest, who struggled courageously for their Hungarian homeland, for its freedom and national independence. They gave their last drop of blood fighting gloriously in the battle of Debrecen. 2nd August 1849. Let their memory endure forever. Let them be resurrected through the victory of the ideas they fought for. Erected on 15th March 1885.”

Boros Sándor emlékműve 1885-ből (fotó: Papp József)

Heroes’ Cemetery

In the second decade of the 20th century, the bodies of thousands more soldiers of various nationalities were buried in Debrecen’s soil. 16 The nearly 1.5-acre, enclosed cemetery of Russian POWs was established next to the former brick factory on the Kokasló mound, on the northern side of the pasture of Köntösgát, at the Nagysándor monument, in 1916 as a cemetery for victims of epidemics, where predominantly Russian prisoners of war but also some Hungarian soldiers 17 were buried, all of whom died of infectious diseases but mainly of cholera.

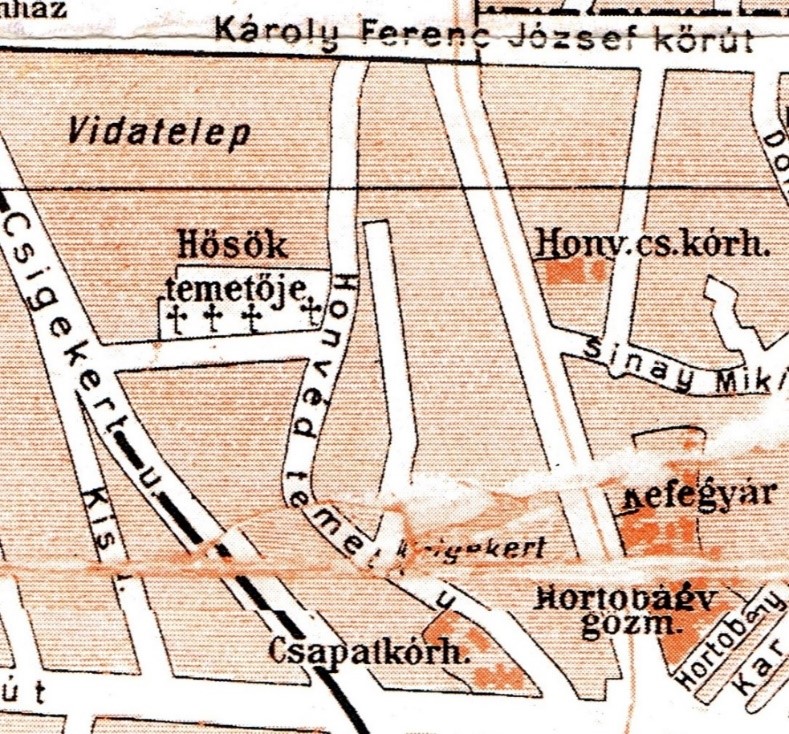

A csapatkórházak és a Hősök Temetője az 1927-es várostérképen

During the war, a large number of wounded soldiers were cared for in the imperial and royal military hospital (today the branch of the county hospital) built on the northern side of today’s Bartók Béla Road (then called Újvárosi Road), in the vicinity of Csigekert. The nearby Military Cemetery, closed at the time, was opened in 1914 to bury the dead soldiers. (18) Honvédtemető (means military cemetery) Street, which led to the cemetery, was given a solid paving in those times. A total of 2,019 soldiers killed in the Great War were buried here. 19 From this time onwards, the reopened Military Cemetery was also referred to as the Heroes’ Cemetery. (Until 1918, the funerals of the heroic dead were regularly attended by the three 1,848 honved veterans from Debrecen.)

Az első iskolai ünnep a Hősök Temetőjében 1915. május 12-én. (Debreceni Képes Kalendárium 1916.)

Many of those who died a hero’s death during WWI were laid to rest in denominational cemeteries. The enclosed graves of the heroic dead in the Hatvan Street Cemetery, closed down in 1932, were tended to up until WWII. (20)

A Hősök Mauzóleuma az 1980-as években (fotó: Vadász György)

The Heroes’ Mausoleum in the Heroes’ Cemetery was completed in 1932. The grandiose building, designed by Jenő Lechner and Pál Szontágh, was built at the highest point of the cemetery, on the top of the Csigedomb hillock. The “Wounded Lion”, which had been built onto the stairs of the mausoleum, was removed and can now be found in the axis of the building.

Debrecen címere a mauzóleum falán (fotó: Papp József)

NOTES

(1) Here: parts of the town.

(2) GAZDAG, István: Hatvanéves a Debreceni Köztemető [The Public Cemetery of Debrecen is 60 Years Old] = Csokonai Kalendárium [Csokonai Almanac] 1994. Db., 1993.

(3) PAPP, József: A római katolikus temető és a temetőkápolna (Régi debreceni temetők) [The Roman Catholic Cemetery and the Funerary Chapel (Old Cemeteries of Debrecen)], manuscript, PAPP, József: Temetőrendezés a 19-20. századi Debrecenben [Landscaping Cemeteries in Debrecen in the 19th and 20th Centuries], manuscript.

(4) HBML – Dvt 264

(5) ZOLTAI, Lajos: Hová temetkeztek a régi debreceniek [Where did Debreceners Bury their Dead in the Past?] - Debreceni Képes Kalendáriom [Debrecen Picture Almanac]. Db., 1933. pp. 80-84, SÁPI, Lajos: Régi temetők Debrecenben [Old Cemeteries in Debrecen] - Hajdú-Bihar temetőművészete [Cemetery Art in Hajdú-Bihar County] (editor-in-chief: Szőllősi, Gyula) VI. Debrecen, 1980. 176.

(6) “Those who died of such perilous diseases must be buried in plots separate from the ‘proper’ burial sites...” - SÁPI op. cit. 181.

(7) SZŰCS, István: A debreceni csata [The Battle of Debrecen] = Csokonai Lapok [Csokonai Papers] 1850. Issues 10, 11, 12.

(8) SZŰCS, Ernő: A debreceni csata (1849. augusztus 2) [The Battle of Debrecen (2nd August 1849)] - Csokonai Kalendárium 1991/1992 178-183., c.f.: ZOLTAI, op. cit., Szűcs, István: Debreczen szabad királyi város történelme III. k. [The History of the Free Royal Town of Debrecen, Vol. 3] - Debrecen, 1871.

(9) 9 Ny 25

(10) VARGA, Zoltán: Debrecen, az orosz megszállás alatt [Debrecen under Russian Occupation] - Sárospatak, 1930.

(11) PAPP, József: A Bek-Dégenfeld-Tisza-palota a MÁV debreceni székháza [The Bek-Dégenfeld-Tisza Palace Houses the Central Offices of MÁV in Debrecen] - Budapest, 1997.

(12) Dr CALAMUS (BOLDIZSÁR, Kálmán): A debreceni csatában elesett orosz tábornok sírja [The Tomb of a Russian General Killed in the Battle of Debrecen] - Debreceni Képes Kalendáriom 1948. 87.

(13) Sz. KÜRTI, Katalin: Köztéri szobrok és épületdíszítő alkotások Debrecenben és Hajdú-Biharban [Open-air Statues and Building Decorative Art in Debrecen and Hajdú-Bihar County] - Debrecen, 1977. 27¬.

(14) SÁPI, op.cit.

(15) KAPLONYI, György: Debreceni ércemberek márványjegyek [People of Ore and Signatures in Marble in Debrecen] - Debrecen, 1943.

(16) KAPLONYI, op.cit. p. 176. 3417, mentions heroes killed in WWI who were laid to rest in Debrecen cemeteries.

(17) SÁPI, op.cit.

(18) The cemetery was inaugurated during an official ceremony on 20th January 1915. (A VÁROS [The Town], Vol. 12, Booklet 7. 1 April 1915. p. 2)

(19) Dr ECSEDI, István: Séta Debrecenben - Debreceni kalauz [Taking a Walk through Debrecen - A Guided Tour]. Debrecen, 1927.

(20) SÁPI, op.cit. 180.